At this year’s AMTA 2025 conference, I presented some research on a simple but overlooked question: what happens when AI interpreters can not only listen, but also see?

Today’s machine interpreting systems, i.e. a specific form of speech-to-speech translation for immediate use, work remarkably well. They can turn spoken sentences in one language into spoken output in another, almost in real time. But they all share a blind spot: they rely only on audio. They hear the words, but they don’t see the world those words belong to.

Humans, of course, never translate speech in a vacuum. We look at facial expressions, gestures, and the surrounding scene to infer all sorts of information. Without that context, even a fluent translation can go wrong.

Why context is everything

Imagine someone in a workshop saying in Italian: “Passami la chiave (key/wrench) on the table”. The machine will most probably translate “Pass me the key on the table”, being key the most common English translation of that word. While the translation system dutifully outputs “key”, but in fact the speaker meant “wrench.” A single word, mistranslated, because the system had no clue it was in a tool shop, where the probability of key meaning wrench is much higher.

Or take a hospital scenario. A nurse tells a parent: “Can you hold her?” A literal translation into a foreign language suggesting to hold the child in one’s arms. But what the nurse really meant was: “Hold her still” for treatment. Only by “seeing” the situation can the system make the right call.

These examples are trivial for humans. For machines, they expose the core limitation of unimodal design.

Building a multimodal interpreter

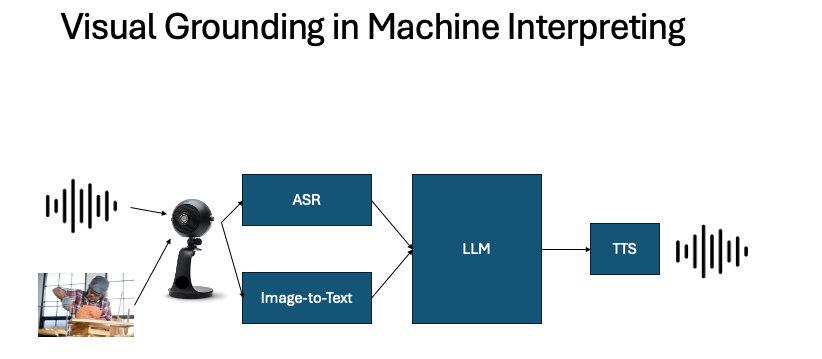

To tackle this, I built a prototype that adds a visual channel to the speech translation pipeline. Here’s how it works:

- Speech recognition captures the words.

- A vision–language model generates captions from webcam input or images.

- A large language model integrates both the speech and the scene description.

- Text-to-speech delivers the translated output.

In other words: instead of treating translation as pure text conversion, the system aims at grounding it in the real world.

Above is a short video clip to illustrate what happens behind the scenes (this is not the user-facing app). In this demo, the AI Interpreter is working in simultaneous mode: it chunks the incoming speech into meaningful units and reconstructs the translation in real time, aiming for a coherent and fluent output. At the same time, the live webcam feed (here replaced with a prerecorded video for reproducibility) captures the surrounding situation and generates a real-time description.

Both the speech and the visual description are then processed together in the translation engine. The image caption, simplified in this demo for the sake of the experiment described below (it normally produces a more structured and detailed format), provides contextual grounding, allowing the system to align its translation with what is actually happening in the scene.

Testing the idea

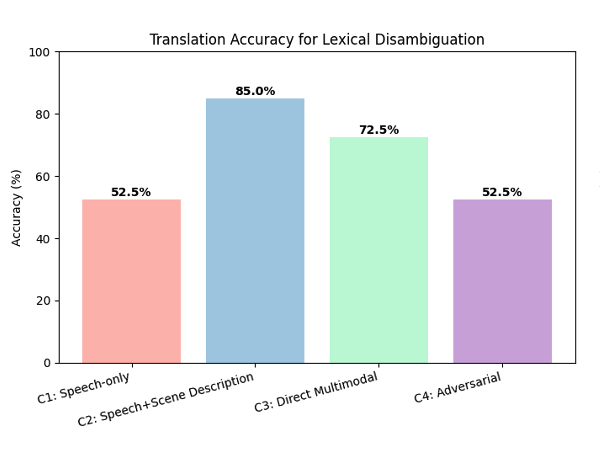

To see if this actually helps, we created a hand-crafted test set of ambiguous sentences paired with images, 120 short utterances that can mean different things depending on context.

The results? Visual grounding significantly boosted accuracy in cases like lexical ambiguity (plaster as “bandage” vs. “cast”). For gender resolution (choosing the right grammatical form), improvements were smaller but noticeable. Syntactic ambiguity (“Paul bought green shirts and shoes”) didn’t improve, because the image alone couldn’t resolve it, or conversely, the LLM still struggles to resolve such kind of ambiguity.

Why this matters

The broader point is that AI interpreting can’t remain audio-only if it wants to approximate real human communication. Adding visual grounding pushes translation closer to how humans actually process meaning: not as strings of words, but as signals embedded in the world.

There’s still plenty to solve, such as scene complexity, vision recognition errors, prompt sensitivity, but the direction is clear. Tomorrow’s AI interpreters won’t just be fluent in languages; they’ll need to be situated agents, interpreting speech in context. Grounding the translation process in the communicative event, I believe, will mark a new stage in machine-mediated human communication with clear benefits for the users.

Full paper: http://arxiv.org/abs/2509.23957

It’s my contention that one of the greatest challenges to adopting any form of AI interpreting, especially when it comes to speech to speech translation, are the compute resources needed to make it run effectively. Widespread adoption in the medium term will likely be hindered by this challenge. This is apparent even by just running speech to text translation when I’m working. For as widespread and readily available that these compute services are, translation surprisingly is not as cheap as the commodity that everyone says that it has become. Compounding this issue of adoption is the Internet connection speed. no doubt that these two bottlenecks will be diminished as adoption increases, but it still seems to me that the technical infrastructure needed for local governments and businesses is outrageously complex. It is obvious to me that the current phase we are seeing where there is fierce competition to build bigger hardware will only suffice up to a point. Ultimately, the AI explosion will lift off once all of this inference can be done locally and I think this is evidenced by the fact that deep seek was able to accomplish training enormous models using first generation hardware, and improving the mathematics. In conclusion, I believe that the shift will happen when there is a team of scientist, have discovered the techniques for recursive self improvement in which the AI itself will reveal mathematical techniques for widespread local inference.

Thanks for the comment. I would say it’s already possible—though still technically challenging—to perform speech-to-speech translation directly on-device. Take, for example, the remarkable Live Interpreting feature on the new Google Pixel (which I’ve tested). A similar approach seems to apply to the new speech-to-speech feature on the latest iPhone (not yet tested). In both cases, the entire inference runs in real time on the device itself. More traditional cascading pipeline can be adapted to be run on consumer computer, but this is (still) hard engineering work. The space is evolving at a breathtaking pace.