Computer-assisted interpreting (CAI) has moved from near invisibility to recurring talking point in both research and professional circles. For most of the history of interpreting, the tools of the trade were minimal: a headset, a notepad, and the interpreter’s cognitive skill. Today, however, computational systems increasingly occupy a place, literally and conceptually, within the interpreting ecosystem. From web conferencing platforms to deliver interpretation from the distance to supportive tools to augment the interpreter, many of these technologies have become a daily companion of most professionals.

The path that led here is neither linear nor uniform. Much like other areas affected by advances in Information and Communication Technologies, CAI has developed through sporadic insights, periods of neglect, and sudden acceleration. The result is a field that is rapidly evolving, yet still marked by gaps, ambiguities, and considerable debate.

This article does not linger on the CAI technology itself, but examines longitudinal trends in research between 2000 and 2025, based on a structured analysis of its corpus bibliography comprising 187 publications (end of 2005)1. Rather than focusing on individual contributions, the aim is to identify macro-patterns in publication output, methodology, technological focus, and, a topic dear to me, interpreting settings.

From marginal topic to consolidated research field

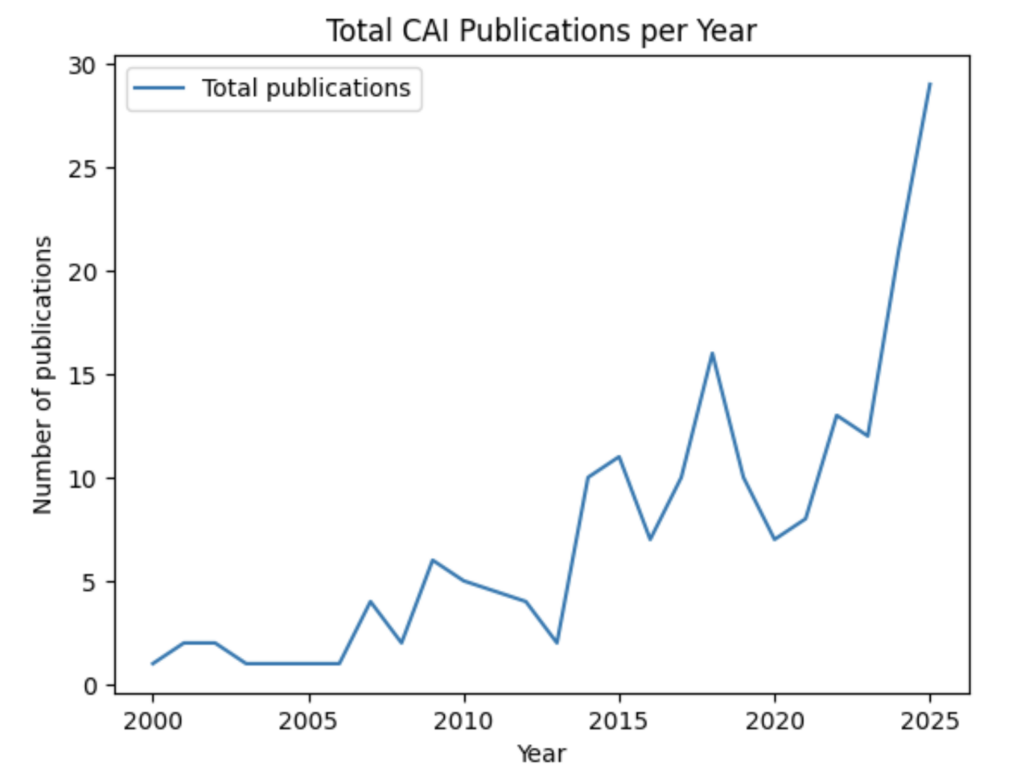

In the early 2000s, CAI appears only sporadically in the literature. Publications are rare and largely conceptual, typically exploring whether computers could in principle support interpreters. For more than a decade, research output remains low and unstable.

A clear shift occurs after the mid-2010s, and becomes unmistakable from 2018 onwards. As fig 1. shows, annual publication numbers increase sharply, reaching unprecedented levels in 2024 and 2025.

This growth signals the consolidation of CAI as a legitimate research domain within Interpreting studies. Importantly, it coincides with the availability of stable tools and infrastructures, as well as with broader advances in language technologies relevant to real-time multilingual communication, especially, but not limited to, speech recognition. 2024–2025 alone account for a very large share of the entire corpus of publications.

From conceptual work to experimental setups

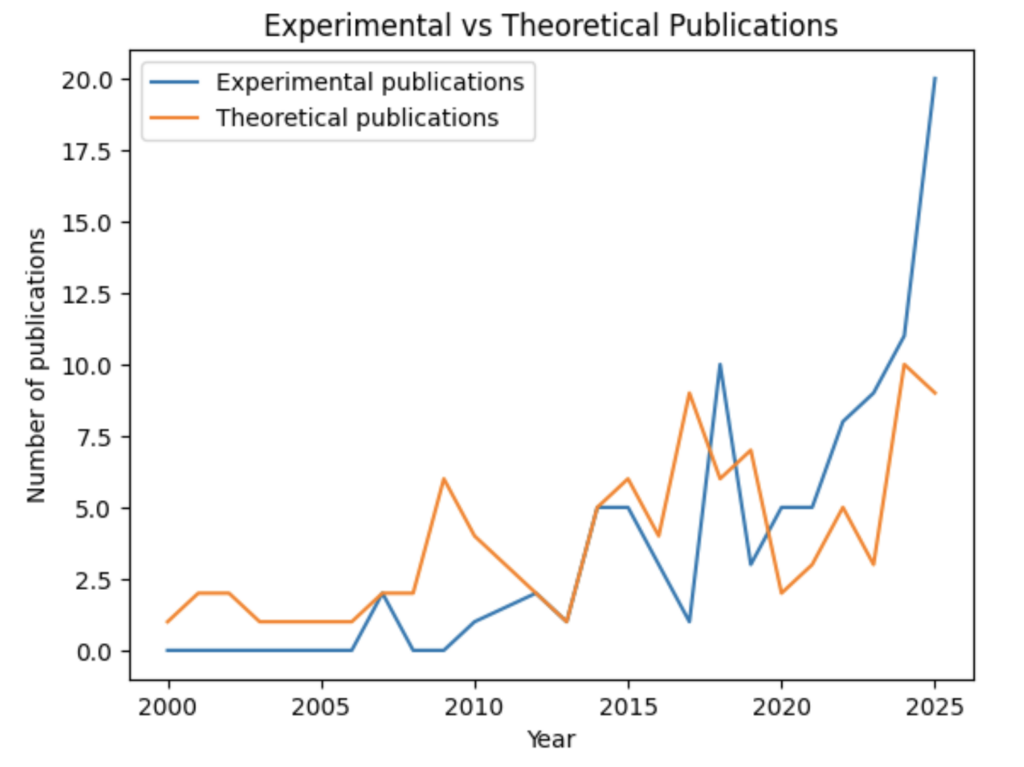

A second major trend concerns research approach and methodology. Until approximately 2014, CAI research is dominated by theoretical and exploratory work. This is unsurprising: before robust tools existed, empirical evaluation was difficult to conduct meaningfully.

The first explicitly experimental CAI studies, written in the context of M.A. thesis at the University of Bologna (Prandi 2015, Biagini 2016) mark a turning point by treating CAI tools themselves as testable interventions, empirically evaluating their effects within interpreter performance and training. From this point on, experimental studies begin to increase rapidly.

By the early 2020s, experimental publications clearly outnumber purely theoretical and descriptive contributions. This transition reflects the methodological maturation of the field and the request for hands on answers on if and how CAI can really support interpreters during their daily work.

Automatic speech recognition as a structural inflection point

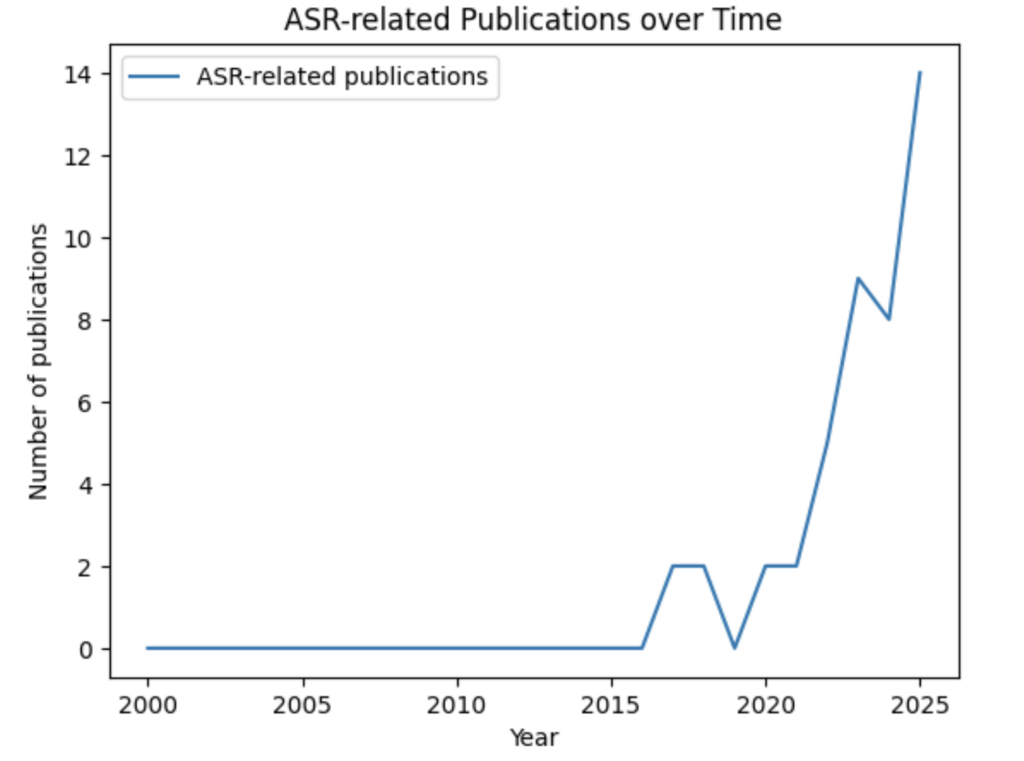

Among all technological factors, automatic speech recognition (ASR) emerges as the most decisive in the last 10 years. Prior to 2016, ASR is virtually absent from CAI research, largely due to insufficient recognition quality for real-time professional use which did not help to spark the idea of using this technology in the daily routines of interpreters. However, improvements in this technological field were soon about to change this.

Fantinuoli’s (2017) first prototype of an ASR-based CAI tool and the publication of Cheung & Tianyun’s pilot study on ASR in simultaneous interpreting (2018) are the first papers in the bibliography to explicitly investigate ASR as a live component of the interpreting process. These contributions represent a genuine inflection point, shifting CAI from static support tools (terminology management) toward real-time linguistic input (live prompting with terms, numbers, etc.).

Subsequent studies consolidate this new research trajectory. Defrancq and Fantinuoli (2020) move beyond feasibility by systematically assessing both system performance and interpreters’ experience in the booth. Shortly thereafter, Pisani and Fantinuoli (2021) introduce controlled experimental designs to measure the impact of ASR on interpreting performance itself.

From the early 2020s onward, ASR-related publications increase steeply and become one of the dominant strands of CAI research. ASR thus acts as a structural enabler, transforming CAI into a real-time cognitive infrastructure and laying the groundwork for later work on machine- and AI-mediated interpreting.

Interpreting settings: a persistent focus on conferences

Despite these change in focus, one pattern remains remarkably stable: over the 25 years, CAI research focuses predominantly on conference interpreting. Public service interpreting (PSI), including healthcare, legal, and community settings, appears later and far less consistently. Even in recent years, PSI-focused CAI studies remain relatively rare.

This imbalance is noteworthy, considering that public service contexts are among the most widespread settings for interpreting and therefore represent a prime candidate for large-scale adoption of technology, including ASR-based tools and AI-mediated interpreting systems. The data suggest that research attention still gravitates toward traditional, high-prestige settings, often mirroring what is taught in university programs, rather than toward domains where interpreting has the greatest societal reach and potential impact.

Important historical dates

| 1993 | Salevsky mentions for the first time the term computer-aided interpreting as an object of inquiry for interpreting |

| 2001 | Valentini writes the first MA Thesis on the use of computers in interpreting |

| 2002 | Stoll writes the first paper on computer systems for simultaneous interpreting, opening up the so-called German school of computer-assisted terminology work for interpreters (among others, Rütten, Will, Fantinuoli) |

| 2016 | Pöchhacker defines Speech Recognition “with considerable potential for changing the way interpreting is practiced” |

| 2017 | Fantinuoli publishes “Speech recognition in the interpreter workstation” de facto introducing the idea (and first prototype) of real-time supporting simultaneous interpreters with suggestions for terminology, numbers, and names |

| 2018 | Cheung & Tianyun publish the first empirical study on ASR in simultaneous interpreting2 |

Concluding remarks

Taken together, these trends document a clear presence of CAI research. The field has evolved from a marginal and largely theoretical topic into an empirically grounded and rapidly expanding area of inquiry. The introduction of robust ASR represents a decisive turning point, enabling new forms of assistance and fundamentally reshaping the scope of CAI.

At the same time, the analysis highlights persistent asymmetries, most notably the continued dominance of conference interpreting, that raise important questions about future research priorities. This imbalance represents a major shortcoming. Researchers should re-direct greater attention toward underexplored, and arguably more socially consequential, domains such as public service interpreting. In these settings, the potential for large-scale deployment of CAI tools is substantial, and experimental evidence is still scarce but urgently needed. More broadly, the field would benefit from opening genuinely new lines of inquiry: too often, research appears to revolve around the same familiar topics, with only minor variations. This pattern is not sustainable if the discipline aims to remain relevant in a rapidly changing technological and societal landscape.

As interpreting technologies become increasingly pervasive, addressing these blind spots will be essential for the continued relevance of Interpreting Studies.

Cited papers

Biagini, G., 2016. Printed glossary and electronic glossary in simultaneous interpretation: a comparative study. Università degli studi di Trieste.

Cheung, A., Tianyun, L., 2018. Automatic speech recognition in simultaneous interpreting. A new approach to computer-aided interpreting.

Defrancq, B., Fantinuoli, C., 2020. Automatic speech recognition in the booth: Assessment of system performance, interpreters’ performances and interactions in the context of numbers. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies.

Fantinuoli, C., 2017. Speech Recognition in the Interpreter Workstation, in: Proceedings of the Translating and the Computer 39. pp. 25–34.

Pöchhacker, F. (2016). Introducing Interpreting Studies (2nd ed.). London: Routledge

Prandi, B., 2015. L’uso di interpretbank nella didattica dell’interpretazione: uno studio esplorativo (Tesi di laurea).

Salevsky, H., 1993. The Distinctive Nature of Interpreting Studies. Target 5, 149–167.

Valentini, C., 2001. Uso del computer in cabina di interpretazione. Università di Bologna, Forlì.

- These bibliometrics are based on the Interpreting and Technology Bibliography freely accessible here: https://www.claudiofantinuoli.org/interpreting-and-technology-bibliography/. ↩︎

- I have never had the opportunity to find and read this paper, but I thought it was worth mentuoning in this brief history of cAI tool research. ↩︎