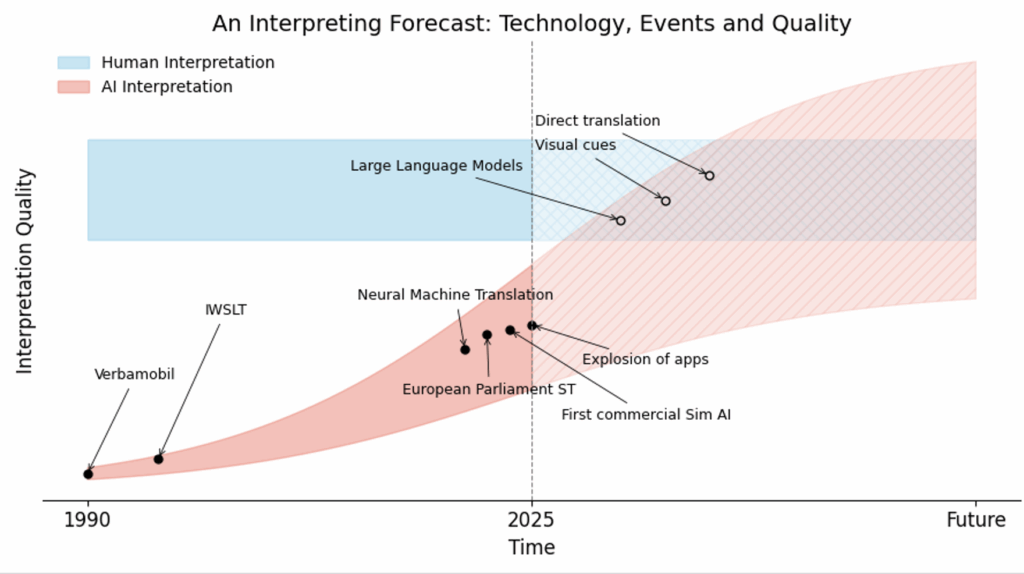

Discussions about artificial intelligence (AI) in interpreting usually revolve around two scenarios: using AI to support human interpreters or developing machine interpreting systems capable of delivering acceptable results on their own. Many stakeholders still doubt whether AI interpreters are realistic at all, while others already accept them as an emerging reality. A smaller group has begun to ask when, rather than if, AI might reach professional levels of quality. My own conservative estimate places this milestone around 2030, though I expect we will see isolated cases of parity well before then.

Yet focusing only on parity risks overlooking a more provocative question. If AI interpreters can match human performance, could they also exceed it, developing abilities that go beyond what even the most skilled professionals can offer? This dimension, rarely considered in current debates, is key to understanding how the interpreting ecosystem may transform and what role human interpreters might retain in the future.

The short answer is yes: AI interpreters will surpass human abilities in several dimensions of interpreting, though not in all, and they will do so in the near future. Put differently, super-human capabilities will begin to emerge at the same time as AI reaches parity with professional interpreters. This prospect matters for anyone considering the implications of having AI agents available for multilingual communication. It is particularly relevant for interpreters and their professional associations, who will need to reflect on how to reposition their role within a profoundly transformed landscape. Before examining the specific areas in which AI agents may develop super-human abilities, a few preliminary considerations are in order.

Benchmarking AI Interpreters Against Humans

Comparisons between human and machine performance are already well established in other fields. In medicine, for example, the diagnostic accuracy of AI systems is systematically evaluated against that of physicians. In transportation, autonomous vehicles are benchmarked against human drivers. Such comparisons serve a dual purpose: they establish thresholds of reliability and safety, and they also clarify where machines may offer additional value. Cost reduction may be one such value, but it cannot be the only one. For instance, an AI system that screens skin lesions might reduce expenses for a health system, but its adoption becomes justifiable only if it also contributes to improved prevention of skin cancer. This is precisely the rationale behind the growing deployment of such systems today.

Interpreting should be approached in the same way. Benchmarks against skilled practitioners are essential not only to assess the credibility of AI systems, but also to determine where uniquely human capabilities remain indispensable and where machines may eventually surpass human limitations. Cost reduction is, of course, a societal benefit (though not for interpreters themselves), but it should not obscure the primary purpose of interpreting: to enable multilingual communication. The crucial question, then, is whether AI interpreters deployed at scale can deliver benefits that go beyond lower costs. One obvious advantage is accessibility: putting a personal interpreter into everyone’s pocket. Yet in professional contexts the situation becomes far more complex and sensitive. And it is precisely here that the prospect of super-human abilities becomes most relevant, since it may alter not only the economics but also the very expectations of what interpreting can achieve.

Potential Areas of Super-Human Performance

When we speak of super-human abilities in interpreting, we do not mean that machines will become “better interpreters” in every respect. Human interpreters possess embodied presence, flexibility, and relational skills that no system will be able to replicate in the short term. But there are several dimensions where AI systems may soon exceed, or in some cases already have, human limitations and, in doing so, redefine the boundaries of multilingual communication. Knowing these dimensions is, in my view, indispensable for governing the changes we are currently experiencing. I will list some of them here, without any pretense of completeness:

High precision in terminology and numerical data

Professional interpreters generally achieve high levels of accuracy, but they remain prone to occasional errors with numbers and technical terminology, a phenomenon well documented in the academic literature. Computer-assisted interpreting tools can mitigate this risk, yet they do not eliminate it entirely. By contrast, one of the uncontested strengths of AI systems lies in their near-perfect recall of such data. Given a bilingual glossary, an AI interpreter will consistently employ the specified terminology without exception, and its precision in handling numerical information is virtually flawless. Anyone familiar with professional interpreting will appreciate how often success (or perceived by the users) in high-stakes settings depends precisely on this kind of terminological accuracy. Think, for example, of interpreting at a financial press conference: a misplaced percentage point or mispronounced figure can have real consequences, whereas an AI system can reproduce every number with absolute fidelity.

Robustness in adverse acoustic environments

Human interpreters often struggle in conditions of high background noise, poor microphone quality, or overlapping speech, and in some cases may be forced to suspend interpretation altogether. AI systems, however, are rapidly improving in their ability to process speech under such adverse conditions. Advances in signal enhancement and noise-robust speech recognition suggest that AI interpreters may eventually outperform humans in maintaining reliable output even when the acoustic environment is far from ideal. Consider a hybrid international meeting where participants join with poor headsets from noisy cafés: while even the best interpreters may falter, AI systems could still deliver intelligible output by filtering and enhancing the signal in real time.

Multilingual coverage at scale

Human interpreters typically master two to four languages at a professional level. AI systems, by contrast, can process dozens of languages simultaneously, including low-resource combinations—albeit at varying levels of quality. This capacity extends accessibility well beyond the limits of today’s professional practice. Imagine a humanitarian mission in a disaster zone: with speakers of multiple minority languages present, finding qualified interpreters on short notice is often impossible. An AI system will, at least partially, bridge these communication gaps by supporting virtually any language combination at the touch of a button.

Unprecedented bag of knowledge at their disposal

The most important advice I have always given to my interpreting students is: be curious. To perform well at the highest levels, interpreters need a vast reservoir of background knowledge to draw on. AI systems built on large language models (LLMs) possess precisely this: the most extensive body of knowledge ever assembled, which they can retrieve and manipulate in real time. This means that AI interpreters will always have access to a virtually limitless knowledge base, allowing them to improve their translations across an indefinite range of situations. Imagine, for instance, a scientific conference on a newly emerging field such as quantum biology: while even well-prepared human interpreters may struggle to follow cutting-edge concepts, an AI system can instantly draw on millions of related documents, papers, and discussions to generate contextually accurate output.

Instantaneous domain adaptation

Human interpreters prepare extensively before assignments, but their capacity to internalize large volumes of specialized material is naturally limited. By contrast, AI systems can ingest and operationalize proprietary glossaries, technical manuals, or background documents almost instantaneously, adapting to new domains in real time. Imagine, for example, an interpreter called to a briefing on a new clinical trial: even after hours of preparation, their grasp of the study protocol may remain partial. An AI interpreter, however, could be supplied with the full documentation seconds before the meeting and immediately integrate the terminology, procedures, and key concepts into its output. This ability to mobilize vast knowledge on demand could dramatically expand the range of contexts where interpreting is feasible.

The list might go on…

Beyond these already foreseeable advantages, additional capabilities may emerge (random selection):

- Extended memory and consistency: The capacity to recall and apply information from earlier discourse segments without fatigue or omission.

- Standardized output across contexts: Ensuring uniform terminology, style, and register across multiple interpreters or channels.

- Adaptive personalization: Adjusting delivery (e.g., formality, register, accent) according to single user preferences or audience characteristics.

Conclusions

AI has already surpassed humans abilities is some confined domain, and it is plausible to think that the same will happen in AI interpreting, at least in a subset of dimensions. Highlighting the areas where AI interpreters may achieve super-human abilities is only part of the story. Equally important are the challenges that will persist, perhaps for a long time, and that continue to define the distinctive value of human interpreters, think of how machines struggle with relational dynamics, embodied presence, and the subtle pragmatics of interaction, dimensions where interpreting is not simply about transferring words or meanings but about mediating trust, managing ambiguity, and navigating the expectations of participants. These are not marginal details; they are central to how interpreting functions in diplomacy, healthcare, law, and many other high-stakes settings.

A realistic discussion of the future of the interpreting ecosystem is therefore only complete if it takes broad and diverse perspectives into account, and if it looks ahead. There is no doubt that its future will be shaped by highly capable machines that are emerging in these very months and years, but it will not be a simple choice of one or the other. Instead, it will be a coexistence of differences. Many find it difficult to appreciate the value of a more diverse and richer interpreting ecosystem, and this is understandable.

What matters is not whether machines will join the stage, but how we choose to share it, by safeguarding the uniquely human dimensions of interpreting while embracing the new possibilities that super-human AI abilities may unlock. If guided responsibly, AI interpreting will not only reshape the profession but also deliver significant value for society at large, by lowering barriers to communication and enabling access to multilingual interaction on a scale never before possible.